- Home

- Kate Wisel

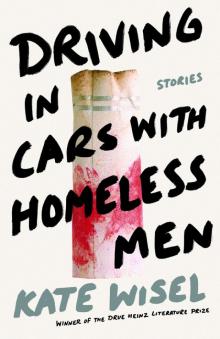

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men Page 2

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men Read online

Page 2

“Thank you,” I say, moving my eyes over the vehicle, his palm balanced over the wheel, the vacuumed upholstery and spotless back seat. It smells new and sick, like sniffing glue.

“So, Miss Serena, can I take you somewhere?” he says.

I don’t know, I think. Can you?

Maybe part of my disappointment lies in the fact that we didn’t meet at the bar holding cold, wet umbrellas, seven shots deep with the stall locked, or online, talking dirty, back and forth, a prolonged handshake in the waiting room, he, my doctor, I, his patient, suddenly braless in his apartment, or at his office, so his wife wouldn’t find out.

We met at the goddamn park. Frankie and I were on the swings, forcing our feet into the sky. We swung to the brink, then leapt off, our bodies like action figures against the fierce heat of the sun, fake crossing ourselves in midair.

He was walking his two-month-old puppy.

“Hi, puppy,” Frankie said, crawling across the playground with wood chips stuck in her palms. “Can we hold him?” she begged.

He bent down, making a crease in his khakis as he released the leash. He grinned as he watched the dog scramble into Frankie’s arms, where it pawed her shoulders, extending its tender belly to lick up her neck like ice cream.

Andrew sat on Frankie’s swing. We watched her laugh, coo, then play dead as her hair sprawled over the wood chips and the puppy struggled across her legs. I made figure eights with my shoe, my grip infant-tight around the chains.

“I’m Andrew,” he said, his nod as determined as a Hitler youth, his eyelashes faint in the sun.

“I don’t want to hold the puppy,” I said.

In the rental car, he leans over the passenger seat and swings open the door.

“Get in,” he says, faking danger like in a rom-com. The wind blows my hair forward for a second. I feel Frankie’s eyes on my shoulder from the sliver of the curtain.

We drive down Beacon Street, past the CVS where I sort of work, and where Frankie and I would be roaming aisles, trying on lipsticks if it weren’t for this. We zoom past the bars we don’t go to anymore because Frankie says they’re infested with college kids, even though we’re college kids.

“I don’t know about you,” he says as he makes a left turn towards the highway, “but I’ve been dying to get out of the city.” The Citgo sign sinks, then disappears completely as we go down through the snake-cage flicker of the underpass.

We’re now on I-93. Maybe I’m still high, but I have to admit, Andrew’s kind of a good driver. He zips in and out of lanes, weaving through vans and four-wheelers with precision. His eyes move from the road to the rearview to me in a narcotized triangle. In my chest is a single tire, asphalt-hot, thwacking forward in a low hum.

But then he turns the radio up and starts drumming the wheel with his thumb, mouthing lyrics to this country song about living like you’re dying. So here I am, trapped in a car with the kind of guy who would slowly then aggressively start singing “Bye, Bye, Miss American Pie” in unison with a bar full of strangers, fists and flipped stools punching the air over their heads. I check him again out of the corner of my eye. He rests his arm around my seat.

I don’t want to know where we’re going. This highway looks like every highway in America, though I’ve never been out of Massachusetts. The truth is I’ve driven down this highway my whole life. Once a month after my parents broke up, my brothers and I driving down I-93, Mom asking us deliberate questions like, “What in God’s name do you eat at Dad’s?”

I’ve told Frankie: When I was nine, my dad moved out of Boston to a rental house by a lake in Gloucester. He had a friend, Sharkey the manager, who would babysit us when my dad was gone. Sharkey had curly hair, the kind that looked wet, and a souped-up motorcycle he would carry me to, on the Fourth of July or after a couple beers. My brothers begged him to let them ride, but Sharkey only chose me, and he drove like dying was the aim, the helmet too big on my head. We zoomed down back roads, slicing free out of the still air. He’d lean to turn, my arms tightening on his waist. I thought of dropping from a plane. The glimpse into endlessness gave my laughter a screaming sound. And the engine burned my shins. The white outlines took on the vertical shapes of crocodiles, poised to belly forward.

After, Sharkey would watch us swim in the lake, that skin on my shins peeling a ghostly white. He hung our bathing suits on the shower rod and dried me off with my dad’s thin towels, taking my legs up on the tub one by one. We watched VHS tapes on the armchair: Problem Child, Coming to America. My hair dried in crimps as Sharkey fell asleep behind me. Sometimes I still feel like I’m in the car while my parents scream in the driveway. My mom had seen the burns on my shins.

“Never again. Never again!” went her raging chant.

But I also used to drive down this highway with Frankie, on the first day Sonic opened or to the mall to buy summer dresses or sometimes just to drive, Frankie blazing up the bowl in a swirl with her knee on the wheel, blowing earrings of smoke rings, with my bare feet up on the dash, sunglasses down to turn the world a purple-black, and blabbing on about how bad we needed boyfriends even though I never felt lonely, then.

I let out a sigh and Andrew looks over at me. He’s sporting puppy eyes, yearning for approval, or, worse, something I can’t articulate. I push the window down a crack, but the air makes a screaming sound, so I seal it back up.

“I’ve never been out of Massachusetts,” I admit.

“Really?” he says.

“Would I lie?” I say.

“You’re mysterious.”

“You’re the one in a rental car,” I say, “driving eighty-five miles an hour towards some town no one goes to so you can, what, dispose of my body in a polluted reservoir?”

We’ve been driving for an hour now. The trees that line the road grow as thick as our silence. My high’s fading fast and I wonder what Frankie’s doing. I text her: I need you like my morning cigarette. I cross then uncross my legs, watch how the clouds pretend to be faces. A monster opening its jaw, crazy gray smoke for eyeholes. I hear a lighter clicking, then Frankie’s hysterical laughter, a laugh like a glass building shattering.

If I were home right now, in our kitchen with the Christmas lights, we might be taking everything out of the fridge and arranging it on the coffee table like a feast. The sun would creep across the hardwood as we’d lay crisscross on the couch, knifing peanut butter onto Oreos, towels twisted tight around our heads. Our faces would be caked in homemade sugar masks, the honey dripping slowly down our necks.

We’d be watching some forgotten movie like L.A. Confidential or Uncle Buck and then, when there was nothing else, repeats of America’s Next Top Model. A commercial for a learning center would come on, an Asian woman with blushed cheeks speaking delicately into the camera as she waved a palm across the facility: “Here at Sylvan, we have a different approach to learning. . . .”

“We don’t learn,” I’d say, “but we approach it.”

Frankie would laugh so hard she’d knock over my water, our fingers Cheeto orange and our bare feet pressed together in a contract.

“What the hell,” I say as we pass a sign that reads, Welcome to New Hampshire. I turn back, gripping the headrest. “We’re in New Hampshire,” I say stupidly.

At the gas station, Andrew unbuckles carefully, the belt zooming across his chest. I think of all the things you can do in New Hampshire that you can’t in Boston: wear flannel earnestly, drive trucks with Republican bumper stickers, carry guns. I flip down the visor and pat my lips with cherry ChapStick, then watch him from the side mirror as gasoline drips steadily from the pump in his hand.

He runs his fingers through his hair and it falls back across his eyes in pieces. I’m thinking, Every veterinarian has a freezer. I’m thinking, I’m being kidnapped, and whatever it is that gets me to seeing him in a muscle tee, tattoos of dead relatives peeking out of the sleeve. There I am, tied to the Motel 6 bed, collarbones making a cavity in my neck as I suck in my breath.

/>

“Shut the fuck up,” he’d say as he cocked his gun. “And do what I say,” he’d whisper, running his dick over my chapped lips.

I bite my nails as we pull out. He jams a CD into the player.

“I used to really like this band Bright Eyes in high school,” he says. Conor Oberst whines as we drive.

I say, “He sounds like Doug Funnie but more suicidal.”

I guess Frankie and I went through a Bright Eyes phase in high school. We did everything. Made out in front of guys, dressed as JonBenét Ramsey for Halloween, gave ourselves loopy tattoos with India ink, laxatives, arrests. With the India ink, we carved “+/−” into the blue of our wrists because Frankie said we’re like batteries, keep each other balanced, charged. She’d lay out wet trash bags on strangers’ roofs to tan, squeeze lemon juice over my head, pluck peach fuzz from my tummy trail, tilt my chin up in the girls’ room mirror, hold me still, slip a needle through my tongue.

But Frankie’s got some kind of itch now. Once we graduate, Frankie says we have to get married. At some point, kids. But when we get divorced and move back in together, what would we do with the kids? I thought. We lived with Nat and Raffa, and now it’s just us, four apartments together and only sometimes I’m worried we’ll keep going like that, apartment to apartment, making figure eights around Boston with our boxes of clattering candles.

Frankie will come home with a kitten that will become a cat, and it’ll die before we do. We’ll bury it illegally in the backyard. We’ll hold vigil candles, our dream catcher earrings drooping our thin earlobes, tatty blankets wrapped around our shoulders like Russian shawls. Frankie will cry, covering her eyes with her fingers, and I won’t know what to say, like the day her mom died.

She’ll slip a stubbed-out roach from her sweater pocket and we’ll blaze up, medical marijuana now ’cause we’re on disability. We’ll pitch cold shovels into the hard dirt as it starts to snow. Our neighbors will swipe back the curtains and call our landlord, adding to their growing list of complaints.

Back in the car, I have to say New Hampshire is a postcard. It’s scenic and lush as it slices by in my window.

“Okay,” Andrew says. “If you could go anywhere in the world—anywhere—where would you go?”

Return of the talk show host. Two can play. I steeple my fingers, then bend back my elbows, but it’s my voice that cracks, “Do you believe in God or is the lack of God your God? If you were stranded on a deserted island, what is the one thing you would never bring? You ever get a girl pregnant?”

“You’re real weird,” he says.

“Case dismissed.”

“We’re almost there,” he says, ticking on the blinker and pulling onto a two-lane highway past all the fast-food signage that glows over the whole road: Get your six inches! Hot ’n’ juicy. Try our new fish bites box.

He parks in a bend in the middle of nowhere. Evergreens reach tall. Power lines rustle with an electric tinge like before it starts to rain, and I hope it does. The rain gets me.

“Follow me,” he says.

We walk up a steep path, snap back branches, and climb up through the trees. We walk forever, falling into a hypnotic, fairy-tale pace, deeper and darker into the woods. The dirt dusts up my shins and sticks in the heat like the skin on a peach. I get thirsty but follow. The back of his neck gleams with sweat.

I once had sex with a stranger in woods kind of like this. We met at a bar and got drunk on PBRs. I whispered, “Let’s go,” my tongue flicking his ear after he spun me around on a barstool, faster and faster, my head thrown back like an over-sugared child. I woke up parched in my then-boyfriend’s bed the next morning. I went to pee and found tiny, incriminating twigs in my hair and in my underwear.

“Are we almost there?” I ask.

We’re both panting when we stop at an opening in the trees. He lifts me up by the waist. We climb onto this rock that ledges out before the drop, so high up it’s like the end of a Jeep commercial. The sky as open as the washed-up wetland below.

“What is this?” I say. “The Grand Canyon of New Hampshire?” I tuck my hands inside my sweatshirt cuffs to hide my smile.

“It’s called Deer Leap.”

We sit at the edge on the weathered granite with our feet kicked off the ledge. From this angle, September comes on thick, the way the heat fades off the grass. But what now?

“This whole thing used to be a pond,” he says, pointing to the deserted valley. “It dried up.”

“Weird view,” I say, the expanse of dead earth gaping under us, “for a voyeur.”

I look up, trying to grasp something enormous, or alive. I want to be this girl who’s taken with the sky, and sometimes I am, so I pull my hoodie up over my head and we kiss.

“You know what I like about you?” he says, taking my chin. I want to slither away, back under the leaves we marched on. “You’re honest.”

I pick up a pebble and squeeze it as hard as I can, chuck it as far as I can throw.

“Want me to be honest?” I say.

“Of course,” he says, shaking my shoulder.

“Your puppy needs a bath. He smells like Doritos.” I pick up another pebble, then steal a glance his way. He’s recovering from the slap, nodding along and smiling too hard.

“More like Smartfood?” he says, his eyes narrowing.

“Can I be actually honest?” I say.

“I don’t know now,” he says, tearing open a pack of nuts from his backpack.

Frankie knows that the first time I masturbated I was nine. In my neighborhood, the kids played after school on this trampoline in my neighbor’s backyard. After I did it, I lay in my bed, holding my hand over my chest to keep my heart inside my body. I could hear the kids shrieking frantically like birds. I remember being seriously worried that they were laughing at me.

One summer I wore gloves to summer camp because I thought I had AIDS.

In high school, Frankie and I went to this rager with an indoor pool. We did mushy coke off the diving board with a senior we barely knew who fed us blueberry Stoli, his arms around us in the hot tub. The next thing I remember I was getting pulled out by the cops. I can still feel the heat on my cheek from the hood of the cop car in the driveway, dripping wet, shivering in Frankie’s bikini. A flashlight clicked and she was already in the back of the car.

The cop had my wrists locked, and I steeled my lower back against his crotch as he bent down to my ear and said, “Have you ever been arrested?”

I tried to pry my arms free and screamed, “Have you ever been raped?”

What if I told Andrew about Sharkey? How he lifted us up out of the armchair and laid me on my dad’s springy mattress, where I waited, stiff as a knife. How he slipped his middle finger inside me like he was separating me from myself. How he laid that same hand on my chest, waiting for my breath, like on a doctor’s table.

“Are you asleep?” he would say.

“Yes.”

Frankie never had a dad, but she understands how the thought of him walking through the door at any second could make you come. I have dreams about Sharkey. We’re in the supermarket, embarrassing everyone in the checkout. Underwater, can’t tell that we’re kissing, our throats filling up with bubbles. In the waiting room, he comes out in a white coat. The supermarket, the kissing, the white coat, night after night. In the white coat, he looks desperate. He’s rushing to me, coming to tell me something critical, but it always stops right there.

Andrew has his arm around my waist as the sun drops fast. He’s stroking the skin above my jeans, and I let him pull my shirt up.

“What does this mean?” he says.

He’s thumbing the DNR tattoo on my rib cage. The most painful place for ink. I look at him, then burst into flames, laughing so hard that I’m afraid I’m going to pee. Andrew watches me, amazed. Frankie says my eyes sparkle when I laugh and that it’s evil and contagious. No one knows me like she does. I swipe up the leaves, tear them to pieces, toss them into the abyss. I fall onto m

y side to catch my breath. Andrew lies next to me, our noses touching, that same, stupid-ass amazement in his eyes. I blink slowly so he can notice mine when they open, and say this instead: “I love you.”

We say it the whole ride home. Him kissing the inside of my wrist with one hand on the wheel, at the toll, grinning at each other dopily while we wait for change, cars honking behind us, at the diner we stop at, the taste of grape jelly on my tongue.

“Can I call you tomorrow?” he says, the car idling outside my apartment. It’s midnight.

“This was great,” I say. “But can you unlock this?”

I bend down to the window because I need a place to lean. Any light between us flickers restlessly like last call. I walk away, knowing what I am. Free as the day God made me, but where’s that guy been?

I climb into Frankie’s bed, where she’s buried, block Andrew’s number, then cling to her pillow, caffeinated from the diner. Awake until it’s light, the birds making frenzied, electronic chirps outside her window.

Later, Frankie’s at her vanity, curling her hair for class. She looks at me in the mirror, our eyes catching. The rosacea on her cheek makes a flustered arc. I lie at the foot of her bed while she twists her hair around the iron. The room swells with the mist of her hair spray, thick lacquer like the rooms of a new house.

“Francesca,” I say, “we should drive somewhere. It’s not that hard to rent a car and move to LA.”

In the corner of the mirror, Frankie’s blush halves. She pulls the curler away, a section of her thick hair bouncing all tame up by her shoulder. I close my eyes and let the spray cover me from head to toe.

“We could become actresses or something,” I say. “No one would even know us.” I hear her lifting her backpack. Zipping her new boots.

“Hang on,” I want to tell her. “I need you like a Tylenol PM.”

Or something more: “I’d carve your name into my arm.”

“I’m a fucking evangelist for your love.”

I press the +/− on my wrist like a button on an elevator that won’t stop dropping.

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men