- Home

- Kate Wisel

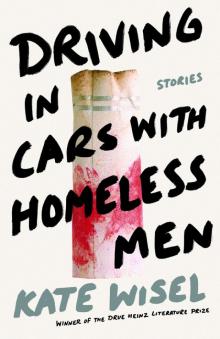

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men Read online

DRUE HEINZ LITERATURE PRIZE

DRIVING IN CARS WITH HOMELESS MEN

KATE WISEL

University of Pittsburgh Press

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. This work is not meant to, nor should it be interpreted to, portray any specific persons living or dead.

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260

Copyright © 2019, Kate Wisel

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 13: 978-0-8229-4568-0

ISBN 10: 0-8229-4568-1

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress

Cover photo: Stephen Gill/Gallery Stock

Cover design: Catherine Casalino

ISBN-13: 978-0-8229-8698-0 (electronic)

For Grace

But the way it happens sometimes is that pain becomes a feed for courage, a nutrient for it: when pain drips steadily, it can embolden.

KEVIN BARRY, “LAST DAYS OF THE BUFFALO”

THERE ARE LITTLE KINGDOMS

CONTENTS

US

HOOPS

SERENA

FRANKIE

SHE SAYS SHE WANTS ONE THING

FRANKIE

CRIBS

STAGE FOUR

RAFFA

BENNY’S BED

WHEN I CALL, YOU ANSWER

SERENA

HOW I DANCE

TELL US THINGS

CALIFORNIA

NATALYA

ENGLISH HIGH

STOP IT

FRANKIE

SHELLEY BENEATH US

GOOD JOB

SERENA

TROUBLE

SADIE ESCOBAR

I’M EXAGGERATING

RAFFA

WHAT COUNTS

MICK’S STREET

RUN FOR YOUR LIFE

Acknowledgments

US

HOOPS

WHEN THE COPS CAME, they came to find us. We huddled by the glittering green sign that said No Loitering. Mozart Park after midnight, on the sidelines in our long-ass sleep tees, watching the boys make free throws in the dark. We were fourteen. We had stubbed butts in our pockets and no curfews.

They’d find us at the packie because we sat with our arms linked on the semicircle stoop. The alkies strutted past, their beards streaks of dirt. We snickered as we rolled crushed Altoids into computer paper. The taste, burnt and crispy, flying up between our lips. Or in the Best Buy parking lot, where we kicked up cartwheels into parked cars. Screamed “O-B-G-Y-N!” to the ladies making their way through the automatic doors, their purses clutched to their sides. On the rocks, we licked the chocolate crusts of Reese’s. Shards of glass in our foam sandals. The clouds sat close. We were roofless. We got bored with the sky and collected trash like criminals. A collage of wet Colt 45 wrappers, warped pages from nudies. Blond girls with their eyes scratched off, their mouths dropped above tits that suffocated their necks.

October we were older. We knew Fetus from the park, where he practiced his amateur boxing. He took us to his garage, where there was a white fridge and a pool table and a concrete floor that smelled like sharp tools. We poured liters of Smirnoff into a watermelon, then shook the chunky liquor in cans of orange soda from Nemo’s. Fetus had sticky, thin lips like the gleam of Smirnoff on the rinds. He’d crouch crow-like on the stool, chalking his cue. He shelled out Oxys like they were mints. The faded shamrock on his neck was a voyeur, a pale green cloud.

One night his mother shuffled in with a greasy ponytail and rhinestone jeans loose like on the rack. She asked us for a lip gloss. In a blurry picture from a disposable camera, she tried to pose with us. Stretched across the green felt, she looked at home among us. We wore hoodies and lip rings, gold hoops that turned our earlobes green. Neon safety vests with no bras. Our pupils pinpointed and bloodshot but shining with purple shadow when the flash caught our blink.

The cops drove slowly down Fetus’s snowy side street. They waited for the snap of a match in the front yard. For a cackle to crack out of the dark. They stood sideways with their shoulders against the garage door, shining flashlights, rapping their knuckles with muscle. They had a sweet tooth for knocking. We squatted behind the torn floral couch as they swarmed, our feet ready as springs. We darted, deft as light. We climbed Fetus’s stairs to tear open the attic window. We pulled each other out like baby teeth, then skidded our butts down the icy roof. We jumped, all four at once. In the patch of snow, an emergency of laughter, one hairline fracture. We were already gone when the track switched and Biggie chuckled: “Fuck all you hos! Get a grip!”

We waited for one another. In the Intrepid outside English High, at the 7-Eleven, outside stalls, the faucet dripping away seconds. We took just as much, ran just as fast, just as far. There were no gardens to trample, planted pathways of blue and purple. Just the rattle of the chain-link after we jumped it.

Winter was a wall we couldn’t see beyond till the garage door moaned when Fetus pulled it, the sky above the triple-deckers dripping colors like splat fruit. If you touched us, we shivered. Our skin like tangerines, on the cusp of bursting.

By spring, the sun vicious on the seats, we were sitting sweaty in the Impala, its rust spots like psoriasis. We circled the Burger King lot, waiting for Fetus. We’d skipped tests, joined zero teams. We didn’t fling ourselves around a track field after the crack of a gunshot. Next spring, in the same BK lot, we heard a cop found some girl in the back seat of a hoopty. He shook her shoulders, shot a vial of Narcan up her nose. She was blacked out, the tips of her fingers ice, so blue they were white.

The dark came every night. Summer came without asking. We were back on the rocks, stumbling, pocketing curled-up candy wrappers fallen from our fingers one whole summer back. Poised to plummet into the woods’ dark center. And beyond the tips of trees, the Boston skyline looked tiny as a postcard in the window of a gift shop we were once kicked out of. The cops never caught us, held our wrists, kept us in their firm, disingenuous, fatherly grips. There was nowhere to sit, so we sat on the rocks, the bright blue thirties, each other. We were skin-close to the sky. Our cheeks against that torn black sheet.

SERENA

FRANKIE

“YOU LIKE BAD BOYS.” That’s what Frankie says.

I used to date a guy with stab wounds on his shoulder I traced in bed while he slept, raised white dashes like the tick of highway lanes. Bad like with toothpicks between their teeth. Idiots really, the kind who wore black hats backward with no logo, walked with a limp, fucked with their tongue out, dropped out of high school, worked at the Sunoco, or security, and got me in for free.

Guys who would text me what up and when I said nothing, you? I never heard back. I liked it when they disrespected their mothers. Or picked me up after school, then dropped me off somewhere discreet, like the back parking lot of a movie theater. I liked them for short, ballistic bursts, so much that if I crossed the street I’d get hit.

I got over boys and went for older guys instead: an investment banker, lawyers, one with three kids and one who kept blueberries in the console of his BMW, a fad diet. In the sunlight, I could see his every pore. He was late for a meeting, so everything was quick. He told me my hips looked like a Coke bottle, and my ass, bent over, a heart. Once he grabbed my cheeks and knocked my head back onto the metal pole in his condo. I liked to press that soft spot behind my ponytail, the dull ache, days later when I was spaced

out at the register.

These were the kinds of men with magazine subscriptions that I flipped through on the train home, licking my finger to flip the thin pages that smelled like the inside of a wooden treasure chest. The last one bought me Summer Jam tickets, one for me and one for Frankie. Frankie went anyway, even though she said, “No clue he was married? Let’s think of a more original lie.”

Frankie could pick a guy out of a lineup even if she wasn’t the witness. That’s what she does: picks. We live together in a two-bedroom split above Sal’s Pizza, where the dopeheads blabber beneath our open windows at night. Sometimes, when I can’t sleep, I crawl into her bed. She lies on her side with her head propped in her palm, her sheets smelling like a department store with the sweet soak of her Guess perfume.

It’s confession, lying there in the dark while Frankie listens. Wrought iron shadows from branches partition the sheet as she points sturdy words like vectors toward my heart. She knows things. She majors in Human Development. That means something to her since we both dropped out of school our first semester, failing being my specialty, then reenrolled the next fall. I don’t really care about school, specifically the part when men walk in and try to educate me.

Sunday and we’re curled into the velvet couch we carried all the way from Goodwill ourselves, then pushed into the corner of our old, enormous kitchen. When I brought this guy Andrew home the first time, I dragged him to my bedroom as Frankie flashed a thumbs-up from the couch. She tells me she likes him because he has natural blond hair and an office job downtown, and takes me to dinner like a real guy. We met in what Frankie calls “a picturesque way.” This is the thing: ever since Frankie’s mom died, she wants everything to go right.

“How did it go?” Frankie says. I’m wearing a softball tee that got mixed up in the laundry and belongs to Frankie. Frankie’s wearing a button-up sweater and a smile that belongs in toothpaste commercials.

“He took me out for Chinese,” I start. I pass back the gravity bong we fashioned from a Pepsi bottle. Her cheekbones flush with rosacea, which makes her look possessed by insider information, like someone’s got their mouth to her ear.

“Details,” she says.

It goes more or less like this: Andrew reached his hands across the booth just as I was about to say, “I have an early dentist appointment in the morning.” The waiter moved to our table with the purposefulness of a surgeon and filled our water, shard-like ice cubes cracking in the silence. Then the food came, platter by platter, clouds of steam swooshing into our faces. I filled my plate and drowned my rice in duck sauce.

“You must have been hungry,” he said as I scraped the last grains with my fork. “Do you want to order dessert?” He leaned forward with the enthusiasm of a talk show host. I ordered another Blue Moon. By the time he got the check I was almost lying down corpse-like in the booth. I stared at him sleepily, exaggerating my blink like a housecat. I contemplated burping but foresaw him refusing the check and thought better of it. Instead, I reached across the table and crushed a fortune cookie in my fist. I straightened up to pick the fortune from the remains, which read: You need only to understand that it is not necessary it understand but only enjoy.

He insisted on walking me home. He tried again to hold my hand as we moved under streetlights that lit up our faces like morons at a spelling bee in which we knew none of the words. I let him grasp my forefinger, which only made me blush.

“Careful,” he said as I kicked my way through the broken glass of me and Frankie’s block, jellied condoms lying shriveled in the cracks. We passed the methadone clinic by Packard’s Corner, where beyond the parking lot the registered sex offenders live in tighter and tighter clusters of red dots like the clap. I was stumbling drunk, and hoped he would leave me at my front door without asking to come inside.

When he did, I said, in my best robot, “I do not have air conditioning.”

We stood in the envelope-littered foyer as he watched me stab keys into my lock. When the door swung open I held my hand on the knob while he waved, tripping down a step as he reversed his way out of my sight.

But I don’t tell Frankie this. I just say, “It’s not going to work out.”

She makes a face, taking the bong between her knees. “This is my last one,” she says. Later on, she wants to study for the first test of senior year. She’s been spending more time in her room, taking notes from textbooks under the clicky green lamp we took from our neighbor’s moving van. Last week, when we were in line at Shaw’s, I was flipping through an Us Weekly, and she said, “You know what’s weird? I think I could actually be a psychologist.”

“Okay,” I said, my nail hooked to my tooth. “Calm down, though.”

She pulls a small hit, the lit aluminum speckled with holes from a safety clip. She watches me as I watch her suck the smoke between her teeth. When she exhales, it vanishes up her nostrils as she bends to put the bong back on the windowsill.

“I thought he liked you,” she says in a strained voice, coughing emphatically with my bad-luck white lighter clenched in her fist. “I thought things were good,” she says again after a long pause.

I dig for explanations: I need space. He’s not my type. He calls me “Miss Serena.” I don’t like his name. Andrew. So kindergarten name tag. Like his parents are still together, paid for his college, take a knee in Christmas cards. Go through his iPod and tell me there’s not a Blues Traveler playlist. He probably strolls into work in some you’re-gonna-love-the-way-you-look-I-guarantee-it fuckin’ suit.”

I catch Frankie looking at me like I’ve turned down the wrong road in my mind only to find her standing there on the other side, tapping her foot.

When Frankie and I first met freshman year of high school, we were both locked out of the basement storm doors of a frat party on purpose. Frankie had a gleaming lip ring that gave her wide eyes a lost but poised look. She was drenched from a forty that got poured over her head, I assumed, for being beautiful.

“Do you smoke?” she asked. Her voice had the sageness of a runaway. I had never had a friend who was a girl. She touched my hand.

“Watch,” she said as she pulled a cigar from her pocket.

Some people remember things like their first kiss. I remember this: us sitting against the shingles of the frat house, our knees up against our chests. Haa-haa, she went, fogging the emptied paper up with her breath like she was trying to keep warm. Then she licked around the tatty edges and sealed the blunt with her lighter, sticking it carefully between my lips. Like that, a candle between us when Frankie clicked. The flame lit her face, a ghost story, her eyebrows darkly arched and expectant.

She said, “Real light, just a little bit.”

I look past her head at the ripped-up billboard that levels with our window. Sometimes it feels like we’re waking up to the same morning, weekend after weekend, the billboard the only thing that changes. Frankie asking me how things went, her red-brown hair wet like leaves down her shoulders.

Frankie, despiser of ambivalence, saying, “So what’s the problem now?”

If there is a problem, a twitching light bulb, a clogged drain, Frankie fixes it herself. No landlord. No phone calls. No foolery. When we shared a car and it snowed three feet, Frankie hurled a shovel under the buried tires, snowflakes like confetti in her hair.

“I think we’re stuck,” I shouted, watching her with a frozen face, hands in my coat pockets as the relentless wind bitch-slapped my cheeks.

“We’re not,” she said automatically. “Grab a shovel.”

My phone buzzes on the coffee table and I ignore it. I know it’s Andrew. Just like I suspected he pocketed our fortunes for a scrapbook. This is what Frankie would die for now, some guy to pose with in pictures, their arms linked like pretzels.

Frankie reaches over for my phone, her lips slightly parted.

“Oh shit,” she says. “He’s outside?” She tosses the phone in my lap, a bomb built just for me. She scrambles across the linoleum in her sweatpants.

“I think that’s him in that car,” she says. She’s got her back against the wall, looking out the window like a secret agent. I brace myself against Andrew’s text: come outside!

“What does he want?”

“Everything,” I say. I go to my room to put on a pair of jeans, a Pats jersey, and my huge-ass gold hoops.

“Serena, wait,” she says. She comes in with her Guess perfume, then dabs at my neck.

“That’s good, that’s enough,” I say. “Am I high?” I ask Frankie, holding on to her forearms. Frankie frowns and genuinely thinks about this. A few minutes ago, we had made elaborate plans to be productive, but I forget what the plans were exactly.

“No,” she says. “I’m high.”

“Okay,” I say, swimming in Frankie’s eye contact. “I’ll be back.” She cups my cheeks with her palms.

“Go,” she says, channeling her mom’s Boston accent, “you whore.” I smile at her, all the way like she’s checking my teeth.

“Be good,” she singsongs. I put my hand on the knob as she shlacks the lock. She makes a point of it. Perhaps I don’t think to lock up because more days than not I wouldn’t mind if one of those dopeheads walked on in and shot me, my face pooled in a salad-sized bowl of Cinnamon Toast Crunch.

“Hey,” I say, bending down to the car where Andrew rolled the window. “You have a car?”

I wrap my arms around my chest, hugging someone. He cocks his head and laughs. Andrew has long, straight teeth, like a dentist’s son. His hair really is blond, which disgusts me. I normally go for guys who are so dark they’re mistaken for terrorists. Making old ladies scowl with their arms around my waist on the T.

“I rented it,” he says meaningfully.

“It’s Sunday,” I say slowly, with equal meaning.

“You look like a rapper’s girlfriend,” Andrew says with that wide smile.

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men

Driving in Cars with Homeless Men